Partisan redistricting suppresses Kentucky voices

March 14, 2022

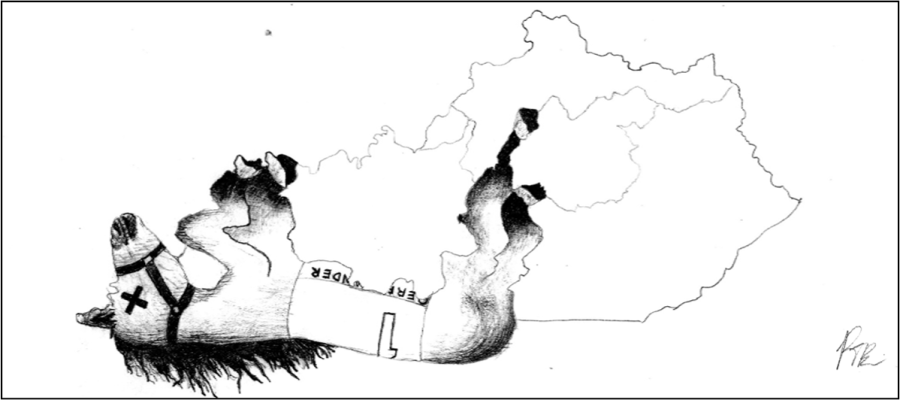

The return of the mythological salamander known as gerrymander is upon us to challenge our democracy.

The word gerrymander is a combination of the name Gerry and salamander. This term was coined when the 1812 Governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, signed a bill that created a partisan district in the Boston area that was compared to the shape of a salamander.

Now what is the process of gerrymandering? Well, once a decade when the Census Bureau releases complete population and demographic data, states and local governments will begin redistricting by drawing new voting district lines.

Gerrymandering—in which politicians take advantage of redistricting to help their friends and party and hurt their enemies by drawing boundaries with the goal of influencing who is elected—is especially prevalent when line drawing is left to legislators and one political party controls the process, as is increasingly the case across the United States.

Gerrymandering allows politicians to pick their voters rather than citizens choosing their representatives.

This is not how a democracy should be run. The politicians that stand to gain the most from reconfigured districts often draw these maps in secret with little public involvement and hope to implement them with little debate.

They are basically telling the public “just trust us” when politicians consistently rank at the bottom of lists of most trusted professions.

Kentucky in particular has recently redrawn maps that are the subject of a lawsuit that alleges gerrymandering.

The Kentucky Democratic Party filed a lawsuit against both the new Kentucky U.S. Congressional map and the new state house of representatives map. The lawsuit claims that the maps are an extreme partisan gerrymander that violates the state constitution.

The suit around the U.S. House of Representatives map focuses on the sprawling and heavily Republican 1st District.

This change removes Franklin County from Republican Rep. Andy Barr’s 6th Congressional District, making the Lexington-based seat slightly more Republican-leaning than the current map and protecting Barr, who looked increasingly vulnerable to Democratic challengers.

Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear vetoed the legislature’s maps, but the Republican-controlled state legislature voted to override his veto.

The effect this process has on communities of color is more drastic, and the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause—which legalized partisan gerrymandering—has exacerbated the problem.

Racial discrimination in redistricting is prohibited under the Voting Rights Act and the Constitution.

However, the Rucho ruling opens the door for Republican-controlled states to defend racially discriminatory maps on the grounds that they were permissibly discriminating against Democrats rather than impermissibly discriminating against Black, Latino, or Asian voters.

A significant change in the proposed state house of representatives map is Covington being cut into small pieces, and those pieces being merged into districts with Republican representatives.

The eastern neighborhoods of Covington were reassigned into Republican Representative Kim Moser’s 64th District, while the northern tip of Covington was pushed into Republican Kim Banta’s 63rd District.

It’s interesting to note that Covington is northern Kentucky’s largest and most diverse city, and it will now likely be without a representative for the first time since the state was founded in 1792.

Affordable housing, economic development, building codes, social services, racial and equality concerns are all issues that are handled differently in Covington than elsewhere in the region. Therefore, this development undermines the views in Covington that need a position to be heard.

The dangers of gerrymandering cannot be overlooked; nonetheless, it is possible to combat gerrymandering and ensure that voters, rather than politicians, choose their leaders.

Limiting the power of self-interested politicians in the map making process by incorporating Independent Redistricting Commissions (IRCs) is one strategy to counteract gerrymandering.

IRCs are independent bodies from the state legislature that are in charge of designing the congressional and state legislative districts utilized in elections. IRCs vary in structure from state to state, but they are generally a voter-centric reform that assures that voters–not politicians–determine political maps.

It is possible for voters to ask for the creation of IRCs through ballot initiatives, as has happened in recent years in Michigan and Colorado.

That being said, voters should take advantage of this and other alternatives in order to safeguard democracy and their political voices from gerrymandering.