Experts say the warm Gulf of Mexico is causing hurricanes to morph into something more hazardous.

According to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the warm gulf is producing intense rainfall, generating bigger storm surges, and causing severely high winds.

As water evaporates from the oceans, it rises and condenses. This change from water vapor to liquid water releases energy that powers hurricanes.

“Hurricanes like heat. They need warm water, and the moist, rising air it produces,” said Benji Jones, a researcher who specializes in climate change and biodiversity loss.

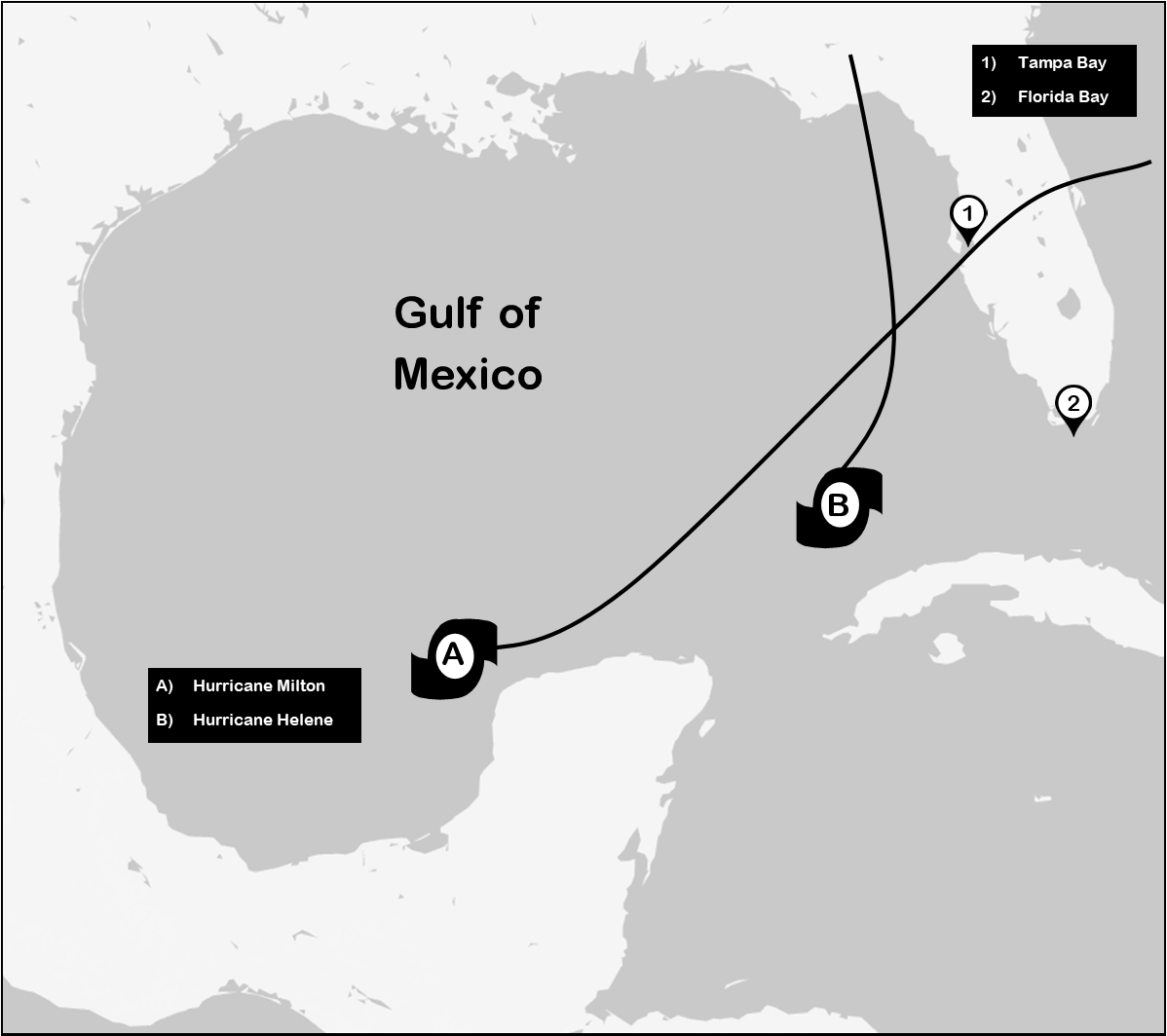

For example, when Hurricane Milton occurred in October it quickly escalated from a tropical storm to a category 5, with wind speeds up to 180 mph fueled by the warm Gulf waters.

“In the Gulf, (Milton) encountered record high ocean temperatures and moist, warm air—the ingredients necessary to intensify,” said Evan Bush, from the NBC News Weather. “The central pressure within Milton’s core dropped at rates one scientist described as ‘insane’ as Milton grew stronger.”

Something similar happened with Hurricane Helene in September.

The water was about 85 degrees Fahrenheit in the Gulf of Mexico when Helene was strengthening.

“The Gulf is now the hottest it’s been in the modern record,” said Brian McNoldy, a climatologist at the University of Miami.

“We’re continuing to see the climatological hallmarks of an active season; sea surface temperatures remain abnormally high,” said Matthew Rosencrans, the lead hurricane season forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

The gulf’s rising heat also contributes to other environmental issues, such as sea level rise and coastal ecosystem damage.

An article from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explained that “the ocean is absorbing more than 90 percent of the increased atmospheric heat.”

The substantial source of global sea level rise is thermal expansion, which is caused when the ocean warms since water expands as it warms.

Warming temperatures cause mountain glaciers and polar ice caps to melt, thereby increasing the volume of water in the oceans.

At the same time, oceans are getting warmer and expanding in volume as a result of this heat (thermal expansion).

According to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, since 1880, the global sea level has risen 20 centimeters (8 inches); by 2100, it is projected to rise another 30 to 122 centimeters (1 to 4 feet).

The temperature in the Gulf is ultimately only a handful of degrees warmer than the historic average, but experts caution that is substantial.

“This is out of bounds from the kinds of variability that we’ve seen in [at least] the last 75 years or so,” said Ben Kirtman, director of the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies.

As scientists are increasingly warning, those degrees matter—a lot. It’s not just sea life that’s at risk, but cities full of people.

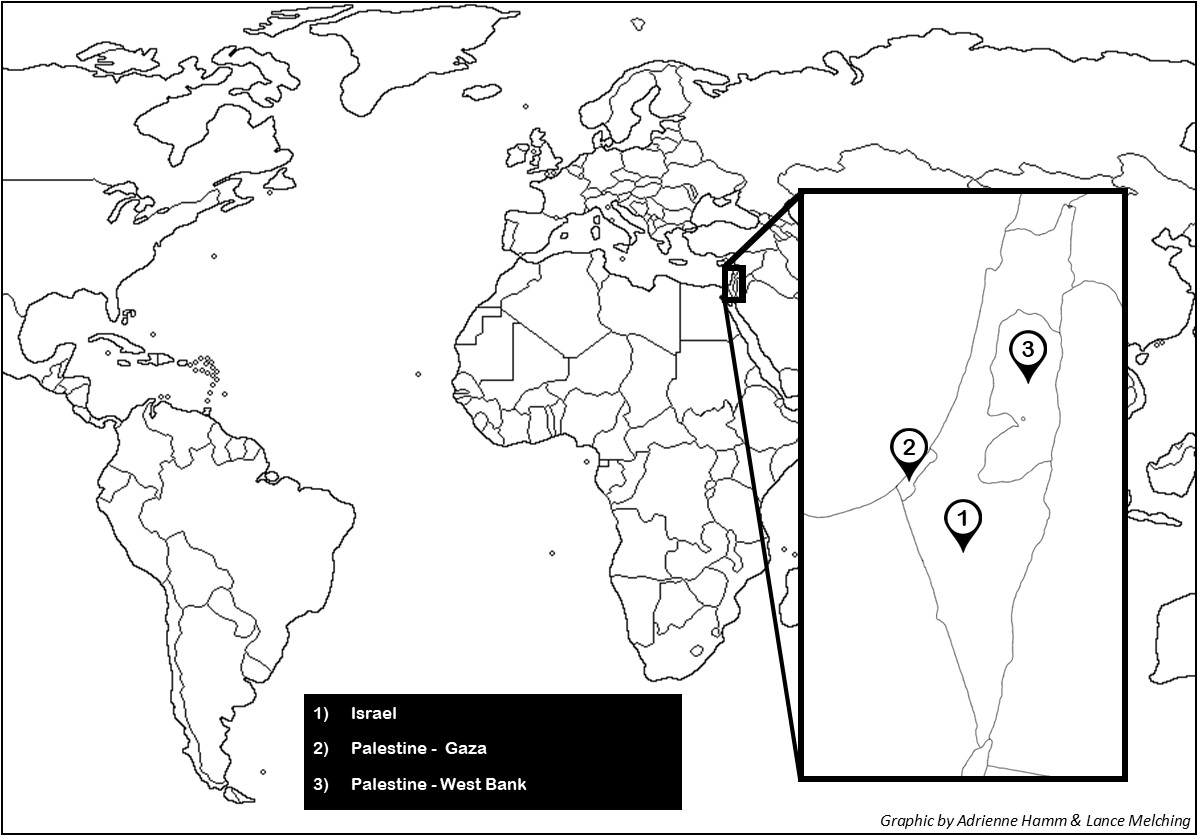

“Then there’s the other problem: hot water kills corals, which defend coastal communities from hurricanes,” Jones said. “These natural structures are large enough to dampen waves that hit the shore, minimizing the threat of storm surge.”

Over the past two decades, sea surface temperatures in Florida Bay, Tampa Bay, St. The Lucie Estuary, and Caloosahatchee River Estuary rose around 70 percent faster than the Gulf of Mexico and 500 percent faster than the global oceans, according to the USF College of Marine Science.